|

Ahnapee -

Algoma Early History

To some people, the Great Lakes are only a large blue mark on maps

of North America with names that are hard to

remember. To those who see them for the first time, the lakes are a

startling expanse of emerald blue water that stretches

beyond the horizon. To the Heuer family, the lakes very much

resembled the Baltic Sea, except that they were fresh water.

To be sure, they had heard the stories of vessels that had

disappeared in storms, for the lake waters could be whipped into an

ugly grey-green in a matter of minutes and without warning. But when

the lakes are calm and the spring storms have passed,

as it might have been in June 1857, the voyage would have provided

the Heuer family with a panoramic view of their new

country. After the long ocean voyage, where all they saw for weeks

was an endless expanse of seawater, the lake voyage was

a welcome contrast. The scenery along the lake’s shores, of vast

forests as far as the eye could see, broken here and there by

the mouth of a river where the cabins of settlers were sheltered by

the virgin trees, was a beautiful sight and one they would

never forget. There were many schooners on the lake with their sails

full of fresh air, blown toward their destinations with

their cargo of wood, iron ore, coal, and people. Sometimes they

would pass close enough to wave at the crew and passengers

of other boats. The farther west they sailed, fewer and fewer

settlements were seen, especially along the northern shores of

Wisconsin, as the boat hugged the western shore of Lake Michigan on

its passage south to Milwaukee, their destination.

Although they did not know it at the time, they more than likely

passed very near where the family would eventually settle.

This lake voyage must have been an exciting and awesome experience

for these early immigrants. Even today, a trip by

sailboat from Buffalo to Milwaukee would be the envy of many.

Upon reaching Milwaukee, they searched for

a temporary residence and found one in Cedarburg, Ozaukee County,

Wisconsin situated just north of Milwaukee. They were joined by

Peter, Wilhelmine, and baby Louisa several weeks later.

Johann Friedrich, Peter Bergin, August, Ferdinand, and Johann found

whatever work they could to recoup some of the cost

of the trip, to support themselves, and to add to their savings for

the future purchase of land. There is no way of knowing what they

did, but Cedarburg was a farming community, and they may have been

engaged in that kind of endeavor. They may also have worked in a

factory producing bricks or other construction materials. They

probably joined the First Immanuel Lutheran Church and felt very

much at home with the large Prussian community that had already

settled in the area. Their constant goal, however, was to find the

right place to purchase land and begin farming. It took a little

time to assimilate all the new information they were hearing and

compare it to what they had heard while still in Prussia.

It is appropriate to explain how the state of Wisconsin

viewed the surge of immigrants – more than five million alone from

Germany, including Prussia, who came to America between 1820 and

1900. The Prussians – the Heuers being only one example – lost their

national identity in the record keeping. When Prussia became a

state within the Federation of German states in 1871, known

thereafter as Germany, all Prussian nationals became Germans.

Although there are some records that identify Prussian nationals as

a separate group of immigrants before 1871, they are usually lumped

into the immigrant group classified as being from Germany. This

conversion, from Prussian to German in 1871, may not have been very

important for the children of Johann Friedrich and Catharina Sophia

Heuer because they, no doubt, already considered themselves

Americans. Their parents, however, and those like them who had

lived a large portion of their lives in the country of Prussia, may

have held a fierce loyalty to their mother country and did not

necessarily approve of the new 1871 Prussia, now nothing more than a

German state. Perhaps that explains why so few of them went through

the naturalization process to become citizens of the United States.

Many of their children did, even though they had been born in

Prussia. The next generation who were born in America, automatically

became citizens; and based on the research for this history, many of

them and their descendants have always thought they were of German

descent, not Prussian. For later historians, Prussian and German

were synonymous.

Many Prussian and German immigrants came to

Wisconsin as a result of extensive pamphlet distributions and

advertising

campaigns in German and Prussian newspapers. Friedrich II of Prussia

had forbidden any efforts by other countries to lure

his subjects away, but nonetheless, people were aware of the many

opportunities in America.

Prominent political and social leaders, once they were established

in the state, became very involved in bringing other

men of talent to Wisconsin. A Milwaukee publication, the Wisconsin

Banner, became the leading voice in the movement for

the liberal franchise for foreigners.

The existence of the Wisconsin Bureau of Immigration became widely

known throughout Europe, and its square dealing

strengthened the good name the state had already gained. Although

this office was disenfranchised in 1855, in 1867 the state

re-established a board of immigration. A local committee of three

citizens in each county was appointed by the governor to

assist the board, particularly in making out lists of the names and

addresses of European friends of Wisconsin settlers, so that

state information packages might be sent directly to them.

These state promoters were influential in

directing German immigration to specific areas, hopefully to gain

control

through their numbers and make them German states. However, they

could not consistently agree on the region to be settled;

some desired Texas and Oregon, while the majority favored the

Northwest Territory, then known as the area between the

Mississippi and the Great Lakes. Franz Löher, one of the first

German travelers and a renowned letter writer, advocated the

best place for German settlers was the territory between the waters

of the Ohio and Missouri, and then to the northwest.Credited with writing the so-called “romantic history” of the

Germans in America, he was genuinely interested in the German-American population of the United States. Since he favored a German

concentration in the Northwest Territory, he spoke in

favor of Wisconsin and Iowa for settlement, and if elsewhere, Texas. Stronger pull factors were the favorable

reports sent back in letters to their homeland by the immigrants who

were well

pleased with their location in Wisconsin. The adage, “Nothing

succeeds like success,” characterized the proactive process

that advertised the state and its virtues. Glowing accounts of life

in America became very popular. America was often

described as a classless society with high wages, low prices, good

land, and a non-repressive government. Advertisements

by shipping firms and land-speculation companies also beckoned Old

World peasants and offered special inducements to

entice newcomers. However, relatively few immigrants found the

paradise promised by the ads and the letters home.

Another lure was the climate of Wisconsin,

which was ideal for farming. Although the winters were cold, the air

was

dry, and fevers incident to new settlements, were not as prevalent

as elsewhere. The climate and soil were considered to be

best suited for Germans since it closely resembled what the

immigrants had left in their homeland. Even the farm products

were the same as those raised in Germany for generations – wheat,

rye, oats, barley, and garden vegetables. Moreover, there

was no competition with slave labor, felt to be degrading by the

self-respecting German, who had been attracted by the

reports he had heard of the dignity of labor in America.

Several other causes united in bringing

Wisconsin so large a foreign and particularly a German population.

In the first

place, when admitted to statehood on 29 May 1848, Wisconsin was

unencumbered by any public debts resulting from largescale

infra-structural improvements. Therefore, immigrants had no

immediate burdens of taxation. By this time, Michigan,

Illinois, and Indiana already had large public debts, so immigration

was directed to Wisconsin, Missouri, and Iowa. Secondly,

the constitution adopted by the state was very liberal towards

foreigners. To secure the right of voting, only one year of

residence was required.

Another feature favorable to the German

immigration was Wisconsin’s liberal land policy. Land granted by the

government

for the maintenance of schools was sold at low prices and without

delay to the immigrants. Nearly four million acres of land

were available for the benefit of schools, and the greater part of

these lands were offered for sale at the minimum government

price of $1.25 per acre. Some remote sections of land sold for less,

others appraised higher, and some excellent pieces of

real estate were even sold on credit. Naturally, because the land

policy was so progressive, even the poorest immigrant, after

some years of honest labor, was empowered to assume property rights

and to meet his financial obligations.

Wisconsin’s population more than doubled

between 1850 and 1860. In 1850, the population was 305,391 and a

decade

later it had reached 775,881. Milwaukee in 1850 had 7,271 Germans

out of its total 20,061 residents.

Between 1857 and 1859, the Heuer family

continued working in the Cedarburg area. In and around Cedarburg

there

was much discussion among the immigrants interested in farming about

a new frontier in Wisconsin. The area was accessible

only by boat. It was north of a town called Manitowoc, north of a

village called Kewaunee, and was on a river the local

Potawatomi Indians, members of an Algonquian people, called Ahnepee

(Ahn-ne-pee´) meaning, “where’s the river,” or,

“wolf river.”7 This new virgin land on the banks of Lake Michigan

was covered with forests, with trees of many varieties

including pine, cedar, hemlock, beech, and maple, and with a

sprinkling here and there of oak.

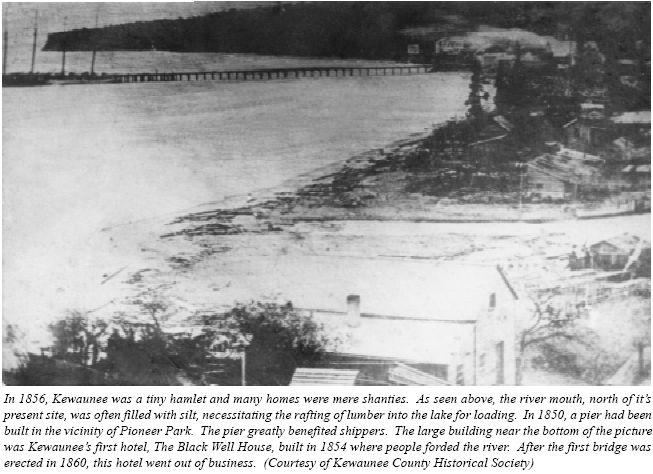

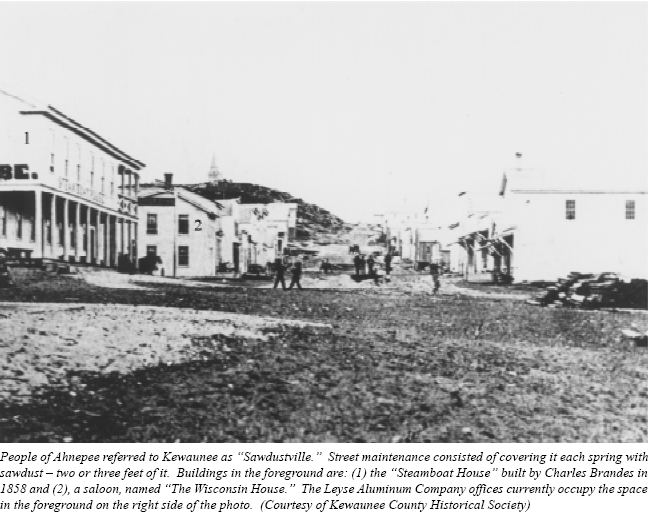

Kewaunee, fourteen miles south of Ahnepee,

was first settled in 1842 when John Vault arrived with his family at

the

mouth of the river known as Kewaunee. The name is derived from two

Indian words, “Ke-weenaw,” which means, “go

around.” It is believed the name came from the fact that in early

times it was necessary, because of the marshes, to have to

go up the river about three miles to ford. John Vault erected a log

cabin and sawmill at this fording place, then and now

called Foot Bridge, and also constructed a dock on the shore of Lake

Michigan to facilitate the shipment of his lumber

products. More settlers followed, and soon Kewaunee was a thriving

community.

The first white person recorded to have

discovered the Ahnepee area was Joseph McCormick. In 1834, he set

out from

Manitowoc with a group of friends in a small boat and navigated the

Ahnepee (then Wolf) River north to the present site of

Forestville. After several days of exploring that northern region,

the group returned to their home in Manitowoc, sharing the

discovery of the newly-found land with the community.

His glowing accounts of the beautiful,

heavily-timbered land, the rich fertile soil, and the abundance of

game caused

many of the new settlers of Manitowoc to strongly consider vacating

their new homes and moving to this place. The idea

waned with the passage of time and was finally abandoned. However,

it had been Joseph McCormick’s desire to obtain the

forty acres of land lying on the south side of the mouth of the

Ahnepee River, knowing that it would someday be valuable

property. Later, those whom he thought were his friends, and with

whom he had shared the experiences of his exploration,

secured the land for themselves. McCormick had the rightful claim on

the land, but it had been lost; he did not visit the area

again until 1855 when he was the first settler in the town of

Forestville, nine miles northwest, up the Ahnepee River.

Records from 1851 show that the first permanent

white settlement began in the region that is now known as Algoma. In March of that year, Orrin Warner and John Hughes (also spelled

Hues), both from Manitowoc, arrived in Wolf River as it

was known at the time. The two young men, both in their early

thirties, had come to Wolf River in their sailboat and

remained one week. They explored the area while living in a tent

made from the sails of their boat, before returning to

Manitowoc.

On 27 June 1851, Edward Tweedale and John Hughes

returned to Wolf River with their families to camp under their

sails. Seven days later, Orrin Warner and family arrived, and the

first white settlers began to prepare a more permanent

shelter. They erected a small shanty on the high ground on the south

side of the Wolf River. It was occupied only about three

weeks when it accidentally caught fire from nets hanging too near

the fire (they had no stoves) and was completely destroyed

together with its contents.

Nevertheless, they persevered and built

another shanty; the three families began the settlement on the land

they had

purchased. Shortly after that, John Hughes built a house on the

bluff north of the river near the lakeshore. It was constructed

of logs and covered with bark. Edward Tweedale erected the second

house on the south bank of the river near where Fourth

Street is today. Orrin Warner followed with his own house nearby.

The houses were without doors or windows for some

time, and in the meantime they were covered with blankets. Lumber to

make the doors and windows had to be brought in by

boat, which had a lower priority than foodstuffs.

The first settlers experienced great

difficulties in obtaining food. The nearest settlement where food

and other necessities

were available was Manitowoc, forty or more miles south. If they

could not go by boat, often the case in the winter months,

they had to travel by foot and to return with the provisions on

their back. They also had to make their own trail, at least as

far as Kewaunee since there were no roads.

The first white child born in the

settlement on Wolf River, and in Kewaunee County, was William

Tweedale, son of

Edward on 10 September 1851. The first vessel that sailed to Wolf River

was the Citizen of Manitowoc. She made several trips to the

settlement in 1851and sailed regularly to this port during the season of 1852,

bringing supplies to the settlers and carrying cargo of ties, posts,

wood bark, and telegraph poles to the southern markets. During the

same season a small trading vessel, the Mary C. Platt,

also stopped several times to supply the pioneers with flour, sugar,

tea, coffee, and other articles of necessity, which could

not be obtained otherwise, except by a trip to Manitowoc on foot.

On 16 April 1852, Kewaunee County was

established by a Wisconsin State Legislative Act. Up to that point,

Brown

County encompassed all the territory north of Manitowoc, including

Door County. A formal county government was not

organized until 1856 when the first county offices were filled by

elected officials. The new county was then divided into

one-square-mile townships.

The area commonly referred to as Wolf River

was officially named town of Wolf by the early settlers in 1852.

From

1852 to 1855, only a handful of new settlers arrived and some of

these were land speculators. Two of these were Peter

Schiesser and Joseph Anderegg. John Hughes sold his large property

holdings to these two men and moved from the area in1855.

Some of the early settlers of the township

of Wolf were American citizens who migrated from nearby Manitowoc,

while

others came from the east. One of these was Abraham S. Hall, a New

Yorker, who claimed to be the fourth settler. He came

to the town of Wolf in May 1852 to erect the first sawmill located

on the south branch of the river, about one-half mile from

the lake. Prior to moving to Wolf, Hall had been engaged in

operating Vault’s mill at Foot Bridge in Kewaunee. His claim

to be the fourth settler was somewhat tainted by the fact he had

already been a resident of the county. Abraham Hall and his

brother Simon Hall, who moved to the township and joined him in his

business on 20 April 1855, operated the sawmill

jointly. They added a gristmill attached to the sawmill, the first

of its kind in the county. Unfortunately, both mills were

completely destroyed by fire around 1870. The Hall brothers, in

1855, also built and fully stocked a store near their mills.

This was the first mercantile establishment in the town.

The following excerpt from an article

titled, “Reminiscences of the Early Days of Kewaunee County” from

the Ahnapee

Record edition of 13 February 1879 told us more:

In the early days of this county, when the country was

sparsely settled, going to mill was one of the many

difficulties which the inhabitants were subjected to.

The first grist mill in this part of the county was

erected by A. S. Hall, in this city (Ahnapee) to which

the people for miles around were obliged to come with

their grain. Mr.Simon Hall tells us that he has often

seen whole families from remote parts of the county come

to his mill with their family of five persons, husband,

wife and three children, who lived some eighteen miles

distant. They started from home at early dawn, the

husband carrying one bushel of wheat, the wife ¾ of a

bushel and so on down to the youngest, all carrying what

they could conveniently. A little girl, the youngest of

the family, for her portion, brought 25 pounds. This

little girl, when placed upon the scales, weighed but 40

pounds herself, and yet she had toiled along with the

others, through the almost trackless forests for 18

miles with a burden over ½ of her own weight.

Many times he has known 75 or 80 people to

be at his mill at once, all waiting their turn. For

their

accommodation he had erected a house near the mill,

where they could shelter themselves from the storm,

prepare their meals or rest during the night. |

The first death in the town, and possibly

the county, occurred in the winter of 1852-53. A young man – a

stranger – on

his way from Manitowoc to some point in the north, arrived at the

residence of Mathias Simons (who really was the fourth

settler) one severely cold afternoon, having been traveling for two

days from Kewaunee to Wolf. He had taken no food or

anything to drink and was not dressed for the weather he

encountered. He spent the night without shelter and his feet, hands,

and some portions of his body and face were badly frozen. The

settlers tried to assist him and alleviate his suffering, but

there was not much they could do for him. He lingered in great pain

for nine days before he died. His name was never

mentioned in the article of this event.

In 1854, the first vessel of any

considerable size to enter the Wolf River, did not hesitate but

sailed boldly up the river

channel. It was the schooner Julia Ann of Racine. She was owned and

commanded by Charles L. Fellows, a resident and

prominent businessman of the town. Among the first settlers were Asa Fowles and

James A. Defaut. These men and their families moved to the township

in

1854. Both families lived on the west side, along what became the

road to Green Bay. James Defaut was later very active

in the town government and would fill many offices of honor and

trust, including Chairman of the Town Board of Supervisors.

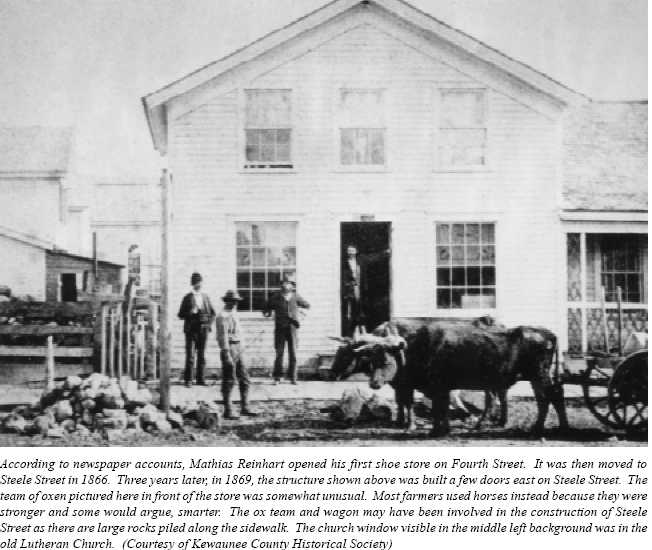

The second store built in the town was a

small board structure owned by David Youngs. It was built in 1855

and stocked

with goods. In 1858, the building was moved across the street and

converted to a private dwelling. Youngs then built the

post office building on the site of his previous store. The front of

the building was used by Mathias Simon, the first

Postmaster, when the town post office was officially established on

4 September 1858. The back was used for Youngs store.

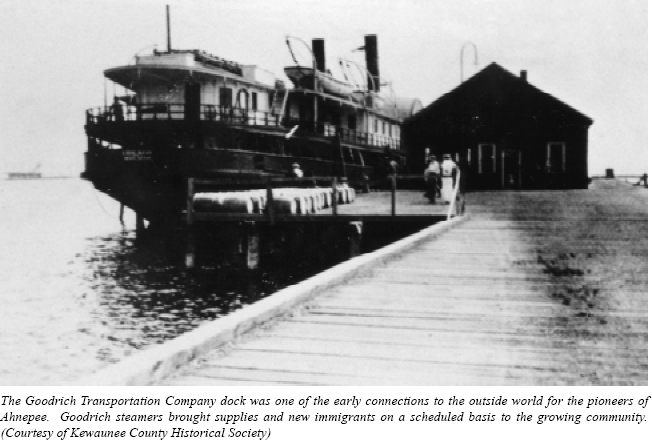

Youngs also built the north pier on the river in 1856. Later, Youngs

would close the store and sell the building and pier to

Charles Griswold Boalt, another early resident who owned a dock on

both the north and south sides of the river and later

served one term as a county judge. His company was an agent for the

Goodrich Transportation Company, owners of many

lake cargo vessels. His business, domiciled in Chicago, was as a

wholesaler of wood, ties, bark, cedar posts, and telegraph

poles. He made a sizeable fortune quickly and purchased a great deal

of property in the town. Judge Boalt would become

known as a member of “the clique,” also known as “the damned

Yankees,” a small and influential group of eastern-born

businessmen who dominated the economic life of the town almost since

its inception.

As early as 1855, eighty-two brigs, 187

barques, and 146 schooners wintered in the Chicago River. There

appeared to

be no lack of water transportation for human or material cargo along

the shores of Lake Michigan. Undoubtedly, many

smaller boats spent the winters in other ports on the lake.

Abraham D. Eveland and his family, also

from New York, moved to the town of Wolf in June 1855. He listed his

occupation as innkeeper. He was a land speculator who also

established an inn shortly after his arrival. He built a large

home on Fourth Street only a short distance from the river. He would

later be involved in politics and government, but his

greatest legacy would be the A. D. Eveland addition to the town of

Ahnapee.

The township of Wolf was growing by leaps

and bounds by 1855. The landscape on the north and south banks of

the

Wolf River had changed forever. Most of the virgin trees had been

cut down, and log cabins dotted the land among the three to

four-foot high stumps that protruded everywhere. On the south bank,

the first visage of an organized settlement was rising

out of the rubble. The land rush had begun. The first Prussian,

German, Belgian, Norwegian, Bohemian, and Swiss immigrants

began arriving in 1855. They kept coming for many years thereafter.

A major portion of the Prussian and German immigrants

came from the northeastern provinces of East and West Prussia –

Pommern and Posen. Most traveled the same route as the

Heuers.

The following is quoted from an Algoma

Record series, “Wolf River, The Remembrances of a Boy and his

Impressions

of our Early Pioneer Life,” found in the 26 August 1910 edition,

originally written by George W. Wing, pioneer and first

editor of the Ahnepee Record:

During the

years of 1856 and 1857, a strong tide of German

settlement turned toward Wolf River and found

lodgment in the town of Wolf several miles west of the

village and upon the fertile lands north of the city.

Many of the settlers came to the Ahnapee area directly

from their native lands, and were entirely unacquainted

with the language and customs of the people that had

arrived before them. The new arrivals were strong and

willing workers who were inured to the frugal practices

in the land they had left. With eager determination,

they

bravely attacked forests of cedar, beech and maple and

carved out small clearings on which to construct their

first homes, crude shelters which were transformed into

log cabins, some of which had roofs made of bark and

blankets carefully hung over door and window openings.

Small garden patches began to take on shape and form.

They were a God fearing people and brought

with them the desire for religious instruction. One of

their

steps, was to contribute enough from their meager

earnings to build two small churches – Lutheran and

Catholic – both standing quite neighborly on the hill

across the river. Theirs was the first settled form of

worship attempted in Ahnapee.

Among these north-side German settlers were

August Kassner, Albert Schmiling, Conrad Zoerb,

Frederick

Heuer, Frederick Damas, Christian Bramer, George Bohman,

Casper Zimmermann, Christian Ebert, August

Schuennemann, John Berg and the Feuersteins. This

settlement was composed of an unusually industrious and

intelligent class of men and women. They fraternized

readily with villagers, and therefore became better

known

in the early days than those living further to the west. |

The

information, though true, was a broad statement about the times but

did not include specifics that records would

explain. For example, it is correct to say that a large group of

German settlers came to Wolf River in the years 1856-1857,

however, not all those mentioned arrived between those years. Other

settler families, besides those mentioned, were the

Melchoirs, Knipfers, Berndts, Densows, Brandts, Raethers, Haacks,

Gerickes, Krauses, Buschs, Klenskys, Shaws, and Bergins

to name a few among the many. There were several different Raether

and Zimmerman families in this first group of pioneers.

This history touches the lives of many of those named.

The first blacksmith in the town of Wolf

was John Roberts who arrived in 1856. He set up a small shop in a

log shanty

in the Sachtlebed’s block near the old Union House. He worked his

trade there for some time and later moved to another log

building near the Second Street bridge. J. M. L. Parker was the first skilled

craftsman who came to town along with his family early in 1856. He

immediately

began working at his carpentry trade, starting the north pier

project.

The first steamboat to appear in the port

was the old steamer Cleveland of Manitowoc. This event on 8 August

1856

was hailed by the new settlers with great jubilation. The boat

brought freight and new settlers to town. On board were

friends, John A. Daniels and Dr. Levi Parsons, who migrated to the

town from New York with their families. Dr. Parsons was

the town’s first medical practitioner and John Daniels, an attorney,

the first representative of the law. Daniels conducted his

business in the same comfortable quarters with Dr. Parsons. In his

profession, Dr. Parsons considered it no task at all to

make house calls starting in the dead of night through the trackless

forests to see a patient some miles away. Fortune favored

the town and the doctor was among the favored, for he was soon

elected register of deeds and conducted business from his

office in a log cabin. The Honorable Lyman Walker would be the

second in the legal profession. John Daniels did not stay

very long for the reason that lawsuits were as scarce as lawyers.

When the members of the new settlement did quarrel, they

saw fit to resolve matters without the aid of five dollars worth of

advice. Lyman Walker became a respected member of the

town and was elected several times to offices of county government.

Another of the earliest settlers was John

Peters who came with his family early in the spring of 1856. He

resided in the

town for several years and then moved to Clay Banks where he lived

for some time, later moving to Forestville.

Peter Schiesser and Joseph Anderegg built the first frame house

erected in the town of Wolf. The house was located on

the south bank of the river on Navarino Street, near John Meverden

and Michael Luckenbach’s tannery and it was later used

as a parsonage.

The building that would become known as the

old Union House, fronting on First Street, was the second or third

frame

building built in the town. It was built in 1856 and was used for a

number of years as a hotel under the name Union House.

Then its builder and owner, Mrs. Lovel, discontinued the hotel

business and used the building as a private residence. It had

been the first structure in town opened as a public hotel displaying

a sign. By 1873, many years later, Mrs. Lovel still lived

there and was planning to put up a new sign and reopen the business.

Other settlers who came in 1856 with their families were William

Balbeck and Mr. Meyers. They labored with their

neighbors and built houses for themselves and their families. Mr.

Meyers stayed only a few years when he and his family

moved to somewhere in the west. William Balbeck’s occupation was a

house painter. He would remain in the town his entire

life.

The education of children had been an

important part of the culture of both Europe and the United States.

The first

settlers of Ahnepee were quick to establish this essential

prerequisite for the future success of their children. Under the

School Law of 1848, free education was supposed to be available to

all children between the ages of four and sixteen years.

The law did not specify a language until 1854 when a new law

specified that the course materials be taught in English. Since

many early settlers came from other areas of the United States and

spoke English, their immediate goal was to find a teacher

and a place to hold classes.

Although the various accounts on the

subject of schools are somewhat confusing, M. T. Parker, in his

serialized, “Historical

Sketch of the Town of Ahnapee,” published in the Ahnapee Record

between July and November 1873, tells us that the first

building used as a classroom was a log shanty on the north side of

the river. The year was 1855. This was not a public school

in the strictest sense because it was formed by the families who

lived in the nearby surrounding area on the north side. The

first teacher hired by the families was Miss Parker who later became

Mrs. George Fowles. Parker goes on to say that the first

building erected in Ahnepee as a public school was a small frame

building on the north side, built in 1856. This school was

located on the bluff overlooking the lake, just north of the house

occupied by the lighthouse tenders, on what is now County

Highway S. The teacher was Mrs. Sanborn, a widow who lived in Door

County. This school was replaced a few years later

with another, larger frame building across the road from the earlier

structure. The first school would later become the

residence of Edward Harkins, who would sell a plot of land to Johann

Friedrich – “Fred” Heuer, son of Johann Friedrich.

In 1858, the residents on the south side of

the river rented a small, one-story building at the foot of Steele

Street for a

schoolroom and hired Miss Irene Yates as their first teacher,

succeeded shortly afterwards by Mr. Ward. A year later, the

school district decided a more permanent school was needed, and in

1859, built a frame schoolhouse on the northeast corner

of Fremont and Fourth streets. Miss Parella Wagner was the first

teacher. When this school was built, in what was then a

clearing with stumps and logs and a high board fence around it, many

settlers complained that the building was too far back

in the country. They were concerned for the safety of their children

during the long trek to school through the wilderness.

The children from Bruemmerville, the Hall Mill settlement, even had

to carry their dinners (lunch) to school. The complaining

did not accomplish much and by 1866, when another school was opened

because of a rapidly growing population, new

settlers had filled in many of the empty spaces on the surrounding

land. A familiar pattern had thus been established. The

paint on the new school had hardly dried when enrollment increased

to warrant greater space – or a new facility.

The first regular election was held in the

township of Wolf on 1 April 1856 in Abraham Hall and Company’s

sawmill.

The election was conducted in the same room used earlier for the

meeting to organize the town. The town at this time

contained scarcely more than a sufficient number of legal voters to

fill all the town offices. Consequently, there was little

trouble obtaining a place on the ticket, and politics and political

speeches were not in demand. The caucus consisted only of

selecting the men most familiar with town business. Following is the

result of this first election:

Supervisors: James

A. Defaut, Chairman, John M. Hughes and D. W. Tery,

Supervisors.

Clerk: Joseph Anderegg.

Treasurer: Simon Hall.

Assessors: Abraham D. Eveland, G. Hind and Peter Schiesser.

Justices of the Peace: S. Chapel, Julius Gregorin, Orrin

Warner and David Price.

Constable: H. N. Smith, Asa Fowles and Abraham D. Eveland. |

The task of organizing a town in the

wilderness was no small feat, and these men deserve a great deal of

praise and

respect for the successful manner in which they carried out their

various duties.

The new settlement was making progress, but

one element of an organized community had not yet been addressed.

The

township had no fire department. The first major fire occurred on

the morning of 12 February 1857. A frame house, owned

and occupied as a dwelling by Frank Feuerstein and Anton Launicker,

caught fire and burned to the ground with all its

contents, despite every effort by the settlers to put out the

flames. It was a considerable loss for the owners as building

materials were not so easily obtained, and worse, household

furnishings were only available from far away Manitowoc.

Even today, with full-time fire departments, the dangers of fire

have yet to be solved.

Another citizen destined for prominence in

the future was G. W. Elliott. He visited briefly in February 1857

alone, liked

what he saw, and returned with his family to stay in June of the

same year. He would take an active part in the further

organization of the town and hold many elected offices.

The first bridge across the Wolf River was

built in the summer of 1857. It was located near the mouth of the

river, about

where Church Street would cross the river if extended across from

north to the south. It had piers on each end and was

constructed of timber. It provided good service for a number of

years but was finally torn down when a new bridge of the

same type construction was built on the Second Street site. Some

planking and timber from the old bridge were used in the

new one. The main reason for doing away with the old bridge was that

it was becoming unsafe; and it was not located in the

central part of town.

And what, one might ask, had happened to all the

native American Indians who had lived and traveled throughout the

Wolf River area? The following article from the 5 September 1968

edition of the Algoma Record-Herald, quoting from the

writings of the late George W. Wing an early pioneer, explains:

|

Visits by Roaming Indians Enlivened Life in Early Algoma

Real blanketed Indians, wearing loincloths,

buckskin doublets and strings of gaudy beads, were at one

time

regular visitors at Algoma. They camped the beaches of the

pioneer settlement, then known as Wolf River, andburied

their dead on the flats at the south end of town. Their

annual dog feasts were occasions not quickly

forgotten by the pioneers, including the late George W.

Wing. A Wing account of the Indian visits follows: There were some early frequenters here,

who, while not exactly habitants were so often upon our

streets and

in our front and back yards that we came to know them pretty

well.

The early Wolf River housewife engaged in

her round of duties would of a day be startled by a creaking

floor

board and turn to find Chenaub or Paw-co-waupee, or Quetetke,

the short-footed joker, within the doorway,hands extended for a “big eat.”

Many a Wolf River child, playing upon the

floor, looked up to see a black, painted face peering in at

the

window. It was always Indian etiquette and good breeding to

look into the window first before trying the door.

These nomads of the forest, Chippewas,

Menominees, Pottawattamies, still claimed the forest round

about

for their game preserves, and paddled their birch canoes, or

sailed their rotten mackinaws with mottled sails up

and down the shores of the lake in apparently aimless and

restless activities.

They were the real blanket Indians, wearing

breech clouts, buckskin doublets, strings of gaudy beads,

and

lived by chance and the chase – heathen, harmless, and much

given to firewater.

One of their early burial places was on the

flats just below the Tweedale hill, and I recall that on

several

occasions they brought the bodies of their dead here in

canoes for burial.

They seemed continually coming and going, but coming

whence and going whither no man seemed to know.

Indeed, they were something like the famous pants Johnny

Karel’s grandmother made for him; when Johnny had them on,

one couldn’t tell whether he was coming or going.

Their camping place was usually upon the

beach just south of the old bridge pier, about where the

water and

electric lighting plant now stands or upon the grassy flats

just north of the river. It was a light order of

housekeeping.

Squaws Did Work

When their canoes or boats grounded upon the beach, the work

of the lazy bucks appeared to be over. They

would jump ashore, throw themselves in luxurious ease upon

the warm sands, while the patient squaws hauled

the boat out, made it secure, tumbled out the wigwam poles

and canvass, the camp kettle and other equipment,

pitched the wigwam, gathered wood and built the fires, and

then went up into the village to collect food from the

settlers for their meal.

Indeed, Quetek, Skeesicks, Paw-co-waupee,

Hochunka, and old Moffou the Drunkard were all wise men

and had learned the science of utilities and were domestic

economists – women must work.

I recall that upon one occasion for several

days various parties from different points assembled here by

land

and water until quite a village of wigwams covered the flats

upon the north side of the river and possible 200

bucks, squaws and papooses had come together. It was the

annual dog feast.

An Indian eats dog in order that he may be

brave, and so it was considered a great compliment to say to

one,

“You dog of an Indian.” “You Indian dog.” However, I

wouldn’t advise anyone to attempt any compliments of

that kind to the modern red man, for he might not understand

the delicate nature of the flattery intended.

Whoops and Yells

After all had assembled one night, they built a great camp

fire, cooked their dogs and consumed quantities of

fire water, after which they made the night hideous with

their whoops and yells, and shouts and singing, and the

various heathen ways of expressing that they were having a

good time.

Eating dog evidently made them brave for

part of the performance consisted in dragging the squaws

around

by the hair of the head, at the same time barking like dogs.

The whites assembled on this side of the

river to witness the pagan performance going on by the

campfire,

with not a few fears that the drunk – mad dog feasters might

take notion to cross over the river and continue their

social festivities in our very midst.

The most thoroughly disgusting party on the

southside of the river was Youngs’ “Old Tige,” who bayed and

howled in rage and disquiet at what he probably felt was a

gross insult and outrage upon all canines.

It was soon after the dog feast across the river;

Youngs’ Old Tige and the boys of the village had never quite

forgiven the dog feasters for their scandalous epicurean

tastes, and whenever afterwards one of them would

appear in the town, Old Tige would pounce upon him fiercely,

while the young white reformers of the village

would throw stones and other missiles at the heathen. It was

our way of expressing disapproval of their kind of

an appetite, and perhaps we also hoped to reform them.

Bigger men having been doing the same thing in working

out other reforms.

Caught Behind Woodpile

Just south across the street from where Swaty’s

store now stands was a long pile of cordwood, and along the

street side of this pile a band of Indians was passing,

industriously worried by Old Tige, while from behind the

pile came showers of sticks and stones thrown by the

youthful Wolf River anti-dog-eaters.

The writer was cautiously peering around one

corner of the woodpile, red handed, when suddenly he felt a

firm grip upon his collar, and looked up in horror and

dismay to find himself the captive of Skeesicks, who had

crept around the woodpile and came up behind stealthily. I

remember that he shook a great deal of my ambition

to be a dog-eating reformer out of me, and I have ever since

maintained and still do that if any one wants to eat

dog, why let him, for all that I care. |

The name of the township of Wolf was changed by a resolution of the

Kewaunee County Board to the town of Ahnepee,

adopted on 10 May 1859. At the same time, the name of the Wolf River

was changed to Ahnepee, and all references to the

old names passed into history.

The transition of the Heuer family, from

Cedarburg, Wisconsin to the township of Ahnepee, is difficult to

relate because

there are no known records that would tell us exactly how it

happened. The article quoted earlier states that many settlers

came directly from their native lands. Many did, but we know the

Heuers spent at least two years in Cedarburg. We believe

they stayed there to work and build up their cash reserves. Peter

Bergin did the same, utilizing his woodworking skills and

saving money to purchase land.

Then, through the information gathered from

the immigrant families who were already settled in the town of

Ahnepee,and from land promoters like John Hughes, Orrin Warner, Peter

Schiesser, and Joseph Anderegg, the decision to migrate

north to this new frontier was an easy one for Johann Friedrich and

Catharina Sophia. Peter and Wilhelmine Bergin, for

reasons of their own, chose to remain in Cedarburg.

The actual migration could have been

accomplished in one of two ways. The men, Johann Friedrich, August,

Ferdinand,

and Johann might have sailed north alone in the summer or early fall

of 1859 to the town of Ahnepee. They would have

found work before they left the dock as there was a great demand for

labor. They would have secured housing and worked

while looking over the area to determine what land was available and

where they wanted to settle. Catharina Sophia,

Ernestine, Bertha, and Augusta would have remained in Cedarburg,

living with Peter and Wilhelmine, with Peter being the

sole support of the family. One or two of the men would have

returned in the spring of 1860 to gather the Heuer family and

bring them to the town of Ahnepee.

The second scenario that follows may be the

most likely considering how close these immigrant families were. In

the

fall of 1859, the Heuer family boarded a boat in Port Washington,

Wisconsin or some other nearby port and sailed north to

the town of Ahnepee. At first they would have stayed in one of the

boarding houses while Johann Friedrich, August,

Ferdinand, and Johann traveled around the area getting the lay of

the land, getting acquainted, and visiting the real estate

offices of Schiesser and Anderegg. Some of the earliest settlers had

already built cabins on their land and begun to clear it,

selling off the timber and other wood products. In some cases, for a

myriad of reasons, these settlers decided to sell their

land and later arrivals, like the Heuers, purchased these partially

prepared homesteads. There were plenty of land deals

being made, keeping Dr. Levi Parsons, the register of deeds for the

township, very busy.

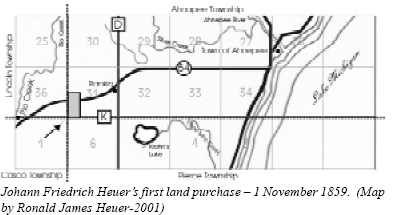

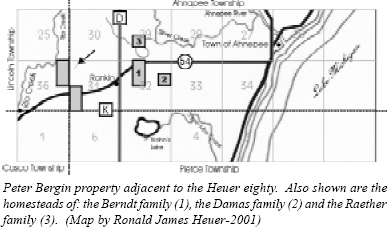

On 1 November 1859, Johann Friedrich

(Frederick Hauer on the deed) purchased eighty acres of land from

William and Caroline Haack for $400.00. On the same date, Johann

Friedrich gave to William Haack a mortgage on the eighty acres in

the amount of $100.00. The land is

described as the west half of the southwest quarter of section

thirty-one, Ahnepee Township, and is located near Rankin, Wisconsin

in the southwest corner of the township. Today, State Highway 54

cuts through the northern third of this land, from east to west,

about two and one-half miles west of the Algoma city limits.

|

|

The value of land had escalated tremendously since 1851. Only eight

years earlier the first land was purchased by John Hughes, Orrin

Warner, and Edward Tweedale for about one dollar per acre. John

Hughes had sold his considerable land holdings to Peter Schiesser

and Joseph Anderegg, no doubt at a good profit. Now in 1859, William

Haack was able to command $5.00 per acre for land that was in the

forest and four miles from the village of Ahnepee. It was easy to

see how the earliest land buyers in the virgin territories of

Wisconsin, who purchased the land from the government, became very

rich, very quickly without lifting a finger except to take pen in

hand. In the case of those that purchased the land in the town of

Wolf – Hughes, Warner, and Tweedale, – it was definitely not that

simple as they actually settled the land, putting themselves and

their families at great risk. The risks paid off handsomely. It is

certain that Schiesser, Anderegg, and others who were early

purchasers made out well because they were able to sell the land in

smaller lots.

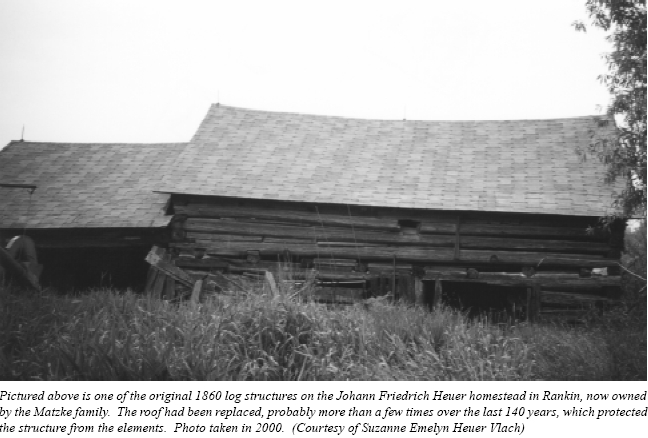

The Heuer homestead had now been established with the

land purchase. It is possible and most probable that William and

Caroline Haack had built a one-room log cabin on the eighty acres

and they may have cleared some of the land. If not, the Heuer family

would have that as their first priority. The Martin Raether family

lived nearby to the east-northeast, the Friedrich Damas family lived

one and one-quarter miles to the east, and the Christoph Berndt

family lived three quarters of a mile to the east. Wolfgang and Anna

Seidl lived on forty acres adjacent to the Heuer land, slightly

north and west. The northwest corner of the Heuer eighty met the

Seidl forty at its southeast corner. They were not out in the

wilderness alone, but it must have seemed that way. The Green Bay

road, undoubtedly nothing much more than a logging trail at the

time, cut through their property. There was already a great deal of

traffic on this road between Ahnepee and Casco, with merchandise

going west and forest

products and produce going east.

|

|

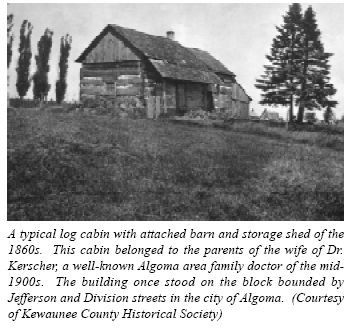

The Heuer family moved to their new land

and occupied the log cabin home, if one existed. They might have

expanded

the size of the cabin since there were two adult parents, three

nearly adult sons, and three daughters ranging in age from

fourteen to four. In the event a cabin had to be built, the four

Heuer men, with the help of some neighbors, would have

accomplished it quickly. By then, building log cabins was much

easier because experienced people were available for

advice. The materials were always close by. This is not to say that

building a log cabin was effortless because it was not.

Many hours were spent shaping the logs and notching the ends

properly. There was a tremendous amount of physical labor

involved in placing the logs and sealing the cracks with mortar.

Instead of bark for the roofs, shingles produced at the local

mills by the thousands were now used. The windows were made of

lumber and opened on leather hinges or maybe even

hinges made of metal. Divided doors were built, a practice brought

from the old country. The upper half could be opened

to let in light and air while the lower half closed to keep out

unpenned animals. This type of door was common, especially

in communities settled by immigrants from Holland and Germany.

|

|

The next task was the building of fences and shelters for the

animals, maybe oxen but more likely horses that were the

most valued possessions a settler could have. They also had a few

cows and raised a few geese and ducks. Every farmer had

a small flock of chickens, laying hens to be more specific, which

provided a steady supply of eggs for breakfast and for

cooking and baking.

It should be noted that Wisconsin had only

become a state in 1848; before that it had been a part of the

Northwest

Territory. Dairy farms were nonexistent in those early years. At

first, the only saleable product from the land was the timber;

it was in great demand for the building of the cities to the south –

Milwaukee and Chicago. Fence posts, timber, bark, and

smaller trees suitable for telegraph poles were all cash crops that

could only be harvested once. Nothing went to waste.

Even the sawdust was used on town streets and country roadbeds to

make them more passable. A major problem was getting

these cumbersome products from the budding farm to the sawmill,

usually located in the river villages like Ahnepee, where

water was used as the power source to run the saws. The sawed lumber

could then be loaded on barges or scows for the trip

south. The sawmill operators employed buyers and crews of men who

went out into the forests, purchased the logs and

posts, and transported them to the sawmill. Of course, the farmer

was not paid a great deal for the wood, no matter what form

it was in, but it was enough to purchase the horses, cattle,

poultry, hogs, and seed necessary to subsist and enhance their

meager, austere living conditions.

Once the outbuildings were completed, the

men began to clear the land, acre by acre. When one considers the

amount

of labor involved in clearing virgin forest with only hand tools, it

is not hard to conclude that the income from it was dismal.

Swinging a double-bitted axe from sunup to sundown, interrupted by

long stints on the end of a two-man cross cut saw, was

probably something to look forward to when considering the

backbreaking drudgery of removing the stumps. The large

trees were felled, trimmed, and sawed into logs of manageable

lengths. They were left where they lay until one of the crews

from the sawmill would arrive with teams of horses and heavy-duty

wagons, or sleighs in the winter, to snake out the logs,

load, and haul them away. Some farmers had enough equipment to do

this themselves, but it was very hard work for horses

and dangerous work for men, work best left to experienced crews with

all the proper equipment.

Large branches and smaller trees were cut

into short pieces to be hauled to the cabin and piled outside for

use as

firewood for the fireplace or stove that was used both for heating

and cooking. The remaining brush was piled at a convenient

place and burned. The only thing remaining was the many tree stumps.

If cutting, sawing, and selling off the

trees was considered hard work, it was nothing compared to removing

the stumps.

To remove the stumps, small or large, the first step was to dig away

the soil from the base of the stump. Then the major roots

were chopped through, one by one, until the stump was loosened. A

rope or chain was then placed around the stump and

attached to the whiffletree of the harness. The team of horses would

then attempt to pull the stump out while one of the men

knelt in the hole and chopped the remaining roots to free it. The

removal of large stumps might take as long as two or three

days, using the same tedious process. The stumps, once removed, were

piled with the brush and burned. If a deep gully,

swamp, or other unusable land was available, the stumps were simply

discarded there. Dynamite would certainly have been

a more efficient, albeit more expensive and more dangerous way of

removing stumps and large rocks, but no mention is

made of it in any of this early period history. It is easy to see

that clearing forty acres took more than one season to

accomplish.

Tilling the new soil was not easy the first

few years because there were still many roots that refused to give

up. And then

there were always the rocks and stones right below the surface that

were constant sources of aggravation for the person doingthe plowing. It was no less fun for those who had to pick them up

and load them on wagons or “stone boats.” Stone boats

were constructed by lashing small logs together into a square that

resembled a raft, onto which the largest, unmanageable

stones were manhandled. A team of horses or oxen, sometimes one of

each, literally dragged the stone boat to a creek bed,

gully, or other untillable area where the stones were piled.

Sometimes there were so many stones that fences were created

with them, especially for those fences that were property lines. The

site of the stone pile had to be selected with some

foresight, because no one wanted to entertain the thought of having

to move them again.

In the spring of 1860, the Heuers planted

their first grain crop on whatever land had so far been cleared and

tilled,

maybe only a few acres. They would have planted wheat as that was

the choice of most farmers in the mid- to late-1800s.They also planted a large vegetable garden near the cabin, protected

with a fence of some kind to keep out the ever-present

rabbits and deer.

During the winter months, when the ground

was frozen, there would have been little to do except care for the

animals.

It is possible the Heuer brothers: August, Ferdinand, and Johann

joined the hundreds of men employed as woodcutters in the

interior and northern forests. They certainly would not have had to

go very far from home because the forests to be harvested

were close at hand. It was an opportunity for them to earn money of

their own for the eventual goal of buying farmland. By

1859, forest products were one of the two principal industries in

Kewaunee County. The other was farming.

The Eighth Federal Census, taken in 1860, records the town of

Ahnepee as having 1,152 inhabitants. The growth in the

population had been a veritable explosion. From three families in

1851, to perhaps 200 people in 1855 when the immigrants

began arriving, was tremendous growth. What happened between 1855

and 1860 was phenomenal. Nine hundred or more

had arrived in five years alone, an average of 180 per year. Of

course, there were many children included in the total, but thenumber over that short period was impressive. To put this into some

perspective, the city of Algoma, 125 years later, had a

population of 3,352, only three times more.

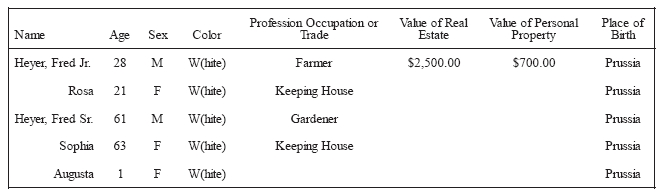

The 1860 United States Federal Census for

Kewaunee County was the first in which the Heuers were counted.

Johann

Friedrich was now using the name Fred. On the 1860 census, the head

of the house was listed as: Fred Heir, fifty-one born

in 1809. His place of birth was given as Germany, and his occupation

was listed as farmer. The value of his real estate

holdings was listed at $200.00 with a personal estate estimated at

$300.00. The entry was as follows:

|

Head |

Fred |

51

years |

Born 1809 |

|

Wife |

Sophia |

52

years |

Born 1808 |

| Son

|

August |

22

years |

Born 1838 |

| Son |

Fred |

19

years |

Born 1841 |

| Son |

Ferdinand |

16

years |

Born 1844 |

| Dau |

Augusta |

5

years |

Born 1855 |

| Dau |

Bertha |

1

year |

Born 1859 |

The census report was grossly incorrect, which was not unusual given

that the Heuers and other immigrants like them

were not fluent in English.9 Johann Friedrich’s birth was in 1808,

not 1809. Catharina Sophia’s name was recorded simply

as Sophia. August was born in 1836, not 1838, and he would have been

twenty-four. The birth order for Ferdinand and Fred– Johann Friedrich Jr. – should have been reversed. Neither dates of

birth were accurate. Ferdinand, born in 1839, was older

than Johann who was born in 1842. Bertha, born in 1849, was older

than Augusta and would have been eleven in 1860. The

information on Augusta seems correct. She was born in 1855, and in

1860 she would have been five.

The census confirmed that the Heuer family

was still together on their homestead farm in June 1860, but there

was one

person missing. Ernestine, now fifteen, was not listed. Further

research of the whole census report revealed she was

recorded with the Abraham D. Eveland family, working as a domestic.

Her name was listed as Tina Hoir, yet anotherspelling of the name from hearing it pronounced. The Evelands had

established an inn near the river in 1855. Ernestine

more than likely worked at the inn and at the Eveland residence

where she boarded, cooked, and cleaned.

After many of

their material requirements such as shelter and food were realized,

the Heuers and other Lutherans of the

small Ahnepee settlement wanted their spiritual needs satisfied as

well. They wanted to belong to a congregation served by

a Lutheran minister. Pastor Gottlief Factmann of the Wisconsin Synod

frequently visited Ahnepee while he was on a

circuitous mission that included areas around Green Bay. Pastor

Factmann, Pastor A. Thiele, and other missionary pastors

visited the early settlers in their homes, or wherever they could

congregate, to preach sermons, administer communion, and

baptize the newborn babies. The missionaries also brought news of

the outside world and provided advice when asked. Thepioneer families appreciated the work of the missionary pastors but

kept the hope alive that they would soon be able toestablish their own church.

Mail was brought from Manitowoc to Two

Rivers, then delivered to Kewaunee, Ahnepee, and Otumwa, the early

name

of Sturgeon Bay, on the back of L. M. Churchill, the mail carrier,

who made the trip on foot. It was said that on one occasion

he made the entire distance of sixty miles from 4:00 a.m. to 8:00

p.m. with the bag on his back. Soon after that, Doc

Vaughan, a Kewaunee liveryman, instituted a weekly stage delivery

service between Green Bay and Kewaunee. That

service was later expanded to also carry freight to Casco,

Coryville, and Walhain in the winter of 1859-60. The volume

increased so rapidly that Vaughn was soon forced to make three trips

weekly.

Transportation of produce, mainly forest

products and grain, was still largely dependent on the vessels that

sailed on

Lake Michigan. There were several steam vessels traveling from

Chicago as far north as Ahnepee. Captain Henry Harkinssailed the Union and Amelia, both vessels owned by Harkins and David

Youngs. Captain Zebina Shaw sailed the schooner

Falcon, and Captain Charles L. Fellows sailed the Whirlwind. Many of

these owners would become well known in the town

of Ahnepee. These vessels were subject to many disasters. One of the

most distressing was the fate of the schooner Union

bound for Ahnepee. It was loaded with $3,000 worth of much-needed

winter articles. The Union filled with water at

Manitowoc and spoiled the goods. The loss of a cargo of winter

supplies meant something to everybody in the county in

those days.

Roads, as a means of transportation, were

being developed but the progress was very slow. In 1858 and 1859,

many

clearings and log houses began to appear along the crude roads that

led from Manitowoc and Two Rivers to Kewaunee.

From Kewaunee north to Ahnepee, only a couple of dwellings broke the

endless forest. Between 1860 and 1870, more

settlers purchased this land, and the trails between the clearings

became the roads of the future. In the low or swampy areas,

roads were constructed using logs. They were called corduroy roads,

and anyone who has ever ridden on one of these will

testify that the name is appropriate.

The first manufacturing facility in the

town of Ahnepee was built in May 1860 by William N. Perry. There

were, of

course, the sawmills and gristmills that changed logs to lumber and

grain to flour, but the Ahnepee Chair Factory was the

first to assemble furniture. The factory was located near the Hall

brother’s mills on the south branch of the Ahnepee River.

While it was being built many Ahnepee businessmen told Perry that it

would be a sure failure. William Perry, not being

easily discouraged went on with the work, completed the building,

put in machinery, and through judicious management,

made it one of the permanent and profitable institutions of Ahnepee.

The factory was enlarged and more modern machinery

and fixtures added. By 1873, it had been sold several times and

resold, and had in fact, passed through the hands of twothirds

of the businessmen of Ahnepee. In 1873, it was owned and

successfully being operated by Joseph Anderegg, John

|

|

Densow, F.

Bublitz, Simon Haag, and Jacob Immel. Anyone with Algoma roots will

remember this engine of the localeconomy as the father of the Algoma Plywood, or simply, The Plywood.

Established in 1892, it has gone through ownership

changes and is now Algoma Hardwoods, Inc., on the street named after

the risk-taking businessman – Perry.

Peter and Wilhelmine Bergin, still in

Cedarburg, would soon join the Heuer family. Peter had been working

and savingmoney for his land purchase. On 21 November 1859, a second daughter

was born, and they had named her Wilhelmine

Alwine Friedricke. She was baptized on 27 November at the First

Immanuel Lutheran Church in Cedarburg. Unfortunately,

the baptismal record did not include her sponsor’s names, which may

have provided a clue as to a possible relationship to the

Heuer family.

The Bergin family was counted on the

Cedarburg, Ozaukee County, Federal Census Report of 1860. It is

certain they

were communicating with the Heuers by letter, and that is how they

found out the Seidls, neighbors of the Heuers, wanted to sell their

land. The Bergins packed their belongings and boarded a boat in Port

Washington, bound for Ahnepee, sometime in the fall of 1860. On 27

December 1860, Peter Bergin purchased from Wolfgang and Anna Seidl,

forty acres of land described as the southeast quarter of the

northeast quarter of section thirty-six in Lincoln Township. The

forty was slightly north and west of the Heuer homestead, with the

northwest corner of the Heuer eighty meeting the Bergin forty at its

southeast corner. Peter and Wilhelmine paid $65.00 for the forty and

received a warranty deed.

|

|

There is little doubt the Heuers assisted Peter and Wilhelmine in

the move and land transaction. The families were

always mutually supportive. The Seidls more than likely had a cabin

on their land but may not have vacated it until the

property was sold. The Bergins may have stayed with the Heuers for a

short time anyway, to catch up on the news, get the

lay of the land, and allow the Bergin daughters to become acquainted

with their grandparents and aunts and uncles. The

Heuer men assisted Peter Bergin to get established by clearing the

land and constructing whatever buildings were necessary.

The two families, now living only a short distance from each other,

shared equipment, supplies, and produce. By the spring

of 1861, the Bergins had settled into their new routine of life,

one-half mile west of Rankin.

The election of Abraham Lincoln as

President and his inauguration in January 1861 was undoubtedly the

subject of

many discussions in Ahnepee around the stoves at the country stores.

The people talked of the possibility of war and were

kept informed by the weekly mail that came to the Ahnepee Post

Office. Everyone knew they would be involved in some

way, and most of the younger men were aware they might be called up

to serve as soldiers. They were no strangers to that

fact. It had been the same in Prussia.

The Civil War began on 12 April 1861 when

Confederate artillery fired on Fort Sumter, but the news did not

reach

Kewaunee County until 14 April, a Sunday, at ten o’clock.

Assemblyman W. E. Finley was a passenger on the Goodrich

steamer Comet, returning to his home from Madison. He brought the

news that, “the war was on,” along with copies of the

Milwaukee Sentinel. It was not until 14 April that the ice embargo

was broken, meaning that now the schooners Albatross,

Mary, and others including the Comet, could finally travel Lake

Michigan and reach Ahnepee. An enterprising young man,

who was the first businessman to establish a paper route, arrived on

the Comet, and from that time on, the people of Ahnepee

and Kewaunee were kept informed with the Chicago dailies: The Times,

Tribune, and Herald every Saturday throughout the

duration of the war.

In May 1861, three weeks after the opening

of the first hostilities between the North and the South, staples

were quoted

in Kewaunee County as follows: wheat 92 cents; oats 23 cents; corn

35 cents; butter 7 to 9 cents; potatoes 23 cents; lard 11

cents; ham 10 cents; shoulders 7 cents. The price of wheat made it

the obvious cash crop for the settler-farmers. The

demand for wheat was high, driving the price up, and it spurred the

settlers to clear their land quickly so they could raise

more of it. The income from the wheat crop was what began to sustain

them as the forest product income diminished.

The first man to enlist – Chauncey Thayer –

was from the town of Kewaunee. After that, many others thought it

would

be a great adventure and followed his lead. It was not until the

Union defeat at Bull Run that the first real effort to secure

recruits was put in motion for 500,000 men in September 1861. Carl

H. Schmidt of Manitowoc opened an office in Kewaunee

to secure recruits for his company in the newly organized German

regiment, the 9th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry. Many

men were volunteering, and recruiting meetings were being held all

over the area.

On 11 September 1861, a third daughter was

born to Wilhelmine and Peter Bergin. They named her Friedricke

Caroline.

We do not know when she was baptized, but the ceremony was

accomplished by a Lutheran minister from Green Bay who

came through the area on an unscheduled basis and handled such

matters for the Ahnepee Lutherans. Johann Friedrich and

Catharina Sophia now had three granddaughters, all belonging to

Wilhelmine and Peter Bergin and all born on American

soil.

The steamer Comet brought several recruiting

officers on 15 September 1861. Their mission was to encourage

enlistment

in the Manitowoc and Kewaunee Rifles Company. Altogether, thirty-six

men from Ahnepee joined the unit, afterward

known as Company K, 14th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. None

of this had much affect on the lives of the Heuer

family, but that would soon change.

By 7 December 1861, Johann Friedrich had

accumulated enough money to pay off the $100.00 mortgage still owed

to

William and Caroline Haack. It must have been a day that fostered

joy and thanksgiving because they now owned the eighty

acres, free and clear. That had been one of the promises of the

opportunities of coming to America, and now it was fulfilled.

The year 1862 brought many changes for the

Heuer family. The war had already taken many local men who

volunteered;

there was already talk of a draft if the war continued. There were

not enough volunteers to fill the ranks of the Union Army.

The Heuer brothers: August, Ferdinand, and Johann were well aware of

this and the probable impact it would have on their

lives. August, the oldest at twenty-five was, by tradition, destined

to stay at home on the farm. Ferdinand, twenty-two and

Johann, nineteen, had accomplished all they could on the farm even

though there was much clearing left to do. Besides, they

were old enough to begin thinking about their own future, and that

would require them to work and earn money for that

purpose. We believe they both decided to become sailors on the Great

Lakes. Although there are no records to substantiate

this with absolute certainty, there is enough information to

indicate this probability. There were plenty of boats sailing into

the Ahnepee River, and the captains were always looking for good

deckhands. The brothers had seen the work of sailors on

the voyage across the ocean and on the Great Lakes, which to them

must have seemed a lot easier than clearing forests.

Maybe the pay was even better; room and board was furnished.

Even though all of the Heuer family members

were now eligible to apply for citizenship, none of them did so at

this

point. For the three brothers, applying for citizenship would have

immediately made their whereabouts known, and that was

not what they wanted if a draft was imminent. Ferdinand and Johann

apparently decided it would be better to be a poor sailor

than a dead soldier.

When the war broke out, Wisconsin had

existed as a state for only twelve years. Of a population of

775,881, more than

half (407,449) were male. In the first year of the war, the state

raised eleven regiments of volunteer infantry. Wisconsin

regiments were part of the forces commanded by Lieutenant General

Ulysses S. Grant and Major General William T.

Sherman. Their performance prompted Sherman to say that he,

“estimated a Wisconsin regiment equal to an ordinary

brigade,” a brigade being at least three times larger or more than a

regiment. By 1862, Wisconsin was sending not only men

to the Civil War battlefields but seventeen million pounds of

much-needed lead, wool for blankets and clothing, and foodstuffs

from two million acres of cultivated farmland.

The war, however, was not causing any

interference with early agricultural pursuits. The 2nd annual County

Fair was

held in Kewaunee. Religious affairs were not at a standstill either.

The German Methodists, in 1861, organized a church in

Ahnepee with Reverend C. G. Becker as their first pastor. Not to be

outdone, the Lutherans in the same area were preparing

to organize, which they did in 1862 with Pastor John H. Brockmann as

their first pastor.

Around this time, Franz Swaty, a merchant

from Two Rivers, established a mercantile business in the town of

Ahnepee.

He brought competition to those already there, but the population

had grown enough to support him. Progress in the way of

transportation and communication was much slower. The first railroad

in the state was a line, built in 1851, which ran

between Milwaukee and Waukesha, a very short distance. By 1862, the

railroad had reached Appleton, the closest station to

Ahnepee. There were still no steamboats that worked the lake during

the winter, and the closest telegraph office was in

Green Bay.

The Union government could no longer fund

the rising costs of the Civil War under the system of taxation in

effect since

the creation of the Treasury Department on 2 September 1789. Over

the intervening years, until shortly after the War of

1812, taxes had been levied on liquor, tobacco, and selected

manufactured items like carriages, harnesses, boots and leather,

beer, candles, caps and hats, parasols and umbrellas, paper, playing

cards, and saddles and bridles; also on watches, jewelry,

gold, silver, and plated ware. But by the time of the Civil War, all

of these had long been repealed and the only ordinary

revenues of the federal government were derived exclusively from

customs. On 5 August 1861, Congress passed an act,

which was primarily intended to temporarily increase duties on

imports, but it also imposed a direct tax of twenty million

dollars to be assessed on land and collected for the government by

the states. That did not stop the hemorrhaging of the

treasury. A new law, passed on 1 July 1862, entitled, “An act to

provide internal revenue for the support of the government

and to pay interest on the public debt,” established a new system of

federal taxation. The Internal Revenue System was born

and shortly thereafter, the first taxes on individual income were

imposed.

Johann Friedrich and Catharina Sophia’s

daughter, Ernestine, became the first Heuer in the family to be

married in theUnited States. She married a progressive and hard working young man

named Heinrich (Henry) Friedrich Wilhelm Gericke

on 4 July 1862, Independence Day. Ernestine was seventeen and Henry

was twenty-seven. Mr. Vandoozer married them in

a civil ceremony since there were no ministers available at the

time. Henry had immigrated to America from Prussia in 1853

with his brother Johann. After first settling in New York and moving

to various other places, Henry finally came to Ahnepee

where he purchased four acres of land from Abraham D. Eveland. The

land was located on the north side, just a block or so

north of where St. Mary’s Catholic Church stands today, and on the

west side of Church Street. Henry was known to the

Heuers as he was affiliated with the Lutheran church and may have

met Ernestine there. She was also working in the town

for the Evelands at the time. Henry built a large home on the four